Day 4

Sunday, 28 March 2010

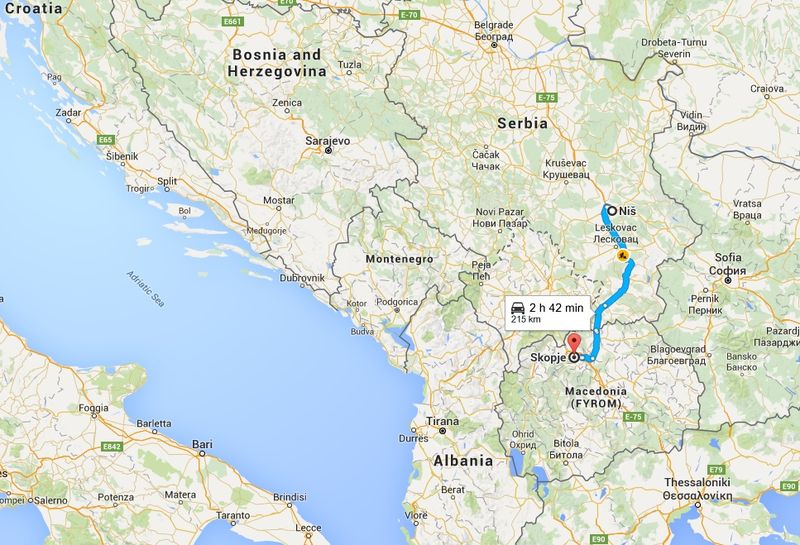

Start: Niš (SRB) 11:45

Arrival: Skopje (MK) 16:45

Total: 234 km

I woke up several times during the night, because the toilet kept refilling itself. Well, nothing's perfect, and I'm sure if we had complained, we would have gotten another room. Room number three then. Or maybe the boss' room again? Might have been fun.

I felt a bit bleary-eyed when we went down for breakfast. Yesterday had been more tiring than I had thought. We were almost alone in the breakfast area. Almost, but not completely alone. There was a group of smoke-aficionados breakfasting on tar and nicotine. How annoying. They happily puffed away and, once again, I could not really enjoy my morning coffee.

We quickly finished our breakfast and stuffed our belongings back into the car. At check out, we noticed that the hotel had charged us 20 euros to register our names with the authorities. I don't mind paying for a service, but they could have told us how expensive it was, or have asked us whether we even required their help with it. We let it pass, but later realized that none of the other hotels on this holiday charged us anything at all for the registration. And to think that I had chosen the Best Western in Niš because I wanted to spend the first night on the Balkans in a “safe” hotel. So much for safe. All you can expect from a American-owned business is that it will happily devise a way to get at your money. All the other hotels on this trip were locally-run establishments and we didn't experience anything of that kind. Quite the contrary.

We decided to visit the Skull Tower on our way out of Niš. But first, we wanted to see some more of this city. We walked around the fortress and quickly found ourselves in a large, bustling marketplace. The day before we had been looking in vain for postcards, so we thought this might be an excellent place to go hunting for them. But Niš is definitely not geared towards tourism: we couldn't find a single postcard to send home. We did find however plenty of great-looking fruit and vegetables. We halted at a stall where two elderly men talked together. We pointed at a bunch of bananas and motioned that we wanted four of them. As that particular bunch contained five bananas, the vendor proceeded to take off one piece of fruit, so that we could have exactly what we wanted.

We hastily assured him that five pieces were fine as well. He weighed the items, labouriously calculated their price and showed us the sum. It was ridiculously cheap. We handed him the money and he patiently counted out the exact change for us. He didn't understand that we wanted him to keep the coins as a tip. Then he put the bananas in a plastic bag and sent us on our way with a smile. Such friendly people!

We left the market and walked towards the city centre south of our hotel. The pedestrian zone with shops and bars lies across a large boulevard, which you can cross via a subterranean passage. That passage turned out to be huge: a network of small tunnels spiders out underground, with dozens if not hundreds of shops and stalls. As it was Sunday, none of them were open, but I can imagine how busy this city underneath the city must be during the week.

The pedestrian zone was not too spectacular on a Sunday morning either, and as there was a fierce wind blowing, we soon walked back to our car and drove to the Skull Tower.

Skull Tower

This time, the building seemed indeed to be open. We paid our entrance fee and walked along the gravel path to the small, round building. The tower may be tiny, but it has four different entrance doors. The first one we tried was locked. Ok, on to the next one. Locked as well. Starting to feel apprehensive, we moved on to the third. And the fourth. All tightly secured. Our hearts sank. The ladies in the ticket booth had only spoken rudimentary English. I didn't feel at all like going back and discussing this with them. We loitered for a few minutes in front of the tower, debating what to do. Just as we had resigned ourselves to asking the ladies for assistance, an elderly gentleman walked up the path towards us. After he had ascertained what languages we spoke, he presented himself, in immaculate French, as our guide for the Skull Tower. He didn't say so, but we had the distinct feeling that he thought we were a bit over-eager and impatient.

First, we small-talked about Luxembourg and France. He seemed to know the latter quite well and we got the impression that he might be a retired teacher of history or French. He told us that Serbia had a traditional cultural affinity to France and that many elder Serbs understand quite a bit of French. What a pity we hadn't known that before, we could have tried French with our market vendor! We learnt more about this Serbian penchant for French culture when we read Ivo Andrić's novel Wesire und Konsuln some years later.

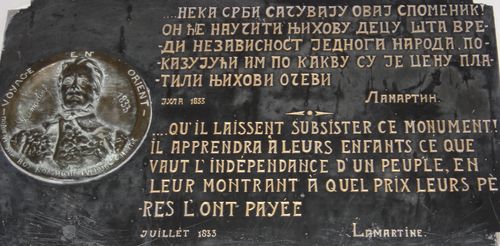

Our guide's explanations about the Skull Tower were very interesting. In 1809, the Serbs, under the leadership of Stevan Sinđelić, had tried to free their country from Ottoman rule. But they had lost the decisive fight, known as the Battle of Čegar, a few kilometers north-east of Niš. The Turkish commander of Niš had the defeated troups beheaded and sent their skulls to Constantinople. There, the sultan decreed that a tower should be built with the skulls, as a warning sign for all future rebels. Originally, 952 skulls were used, but many were later buried and nowadays only about 60 of them remain. The tower stood originally in the open air, but in 1892, a chapel was built around it to protect it from the weather. Thus, a monument that had originally been built as a deterrent to rebels became a symbol of the universal need for freedom and a self-determined life and a national monument to commemorate the Serbs' fight against foreign oppression.

The French poet Lamartine visited the Skull Tower in 1833. Inside the chapel, a plaque shows his comments in French and Serbian. It translates thus: “They should keep this monument! It will teach their children the value of a people's independence, by showing them how dearly their fathers have paid for it.”

After the tour, I wanted to give our guide a tip. But he flatly refused to take any money. He smiled and explained: “We are friends now, aren't we? I am employed to give you the tour and I receive a salary for this. I enjoyed showing you around and there is no need for you to give me money for it. I know that tips are standard practice in your country, but this is not the case here. When people are courteous and hospitable here, it is not because they expect to receive money.” What a difference from my experiences in other, more touristy, places of this world!

Still, I would like to repay the Serbs in some way for the friendliness and hospitality that I experienced in their country. As money won't do, I've decided to do it with this blog: the Serbs are a wonderful people, as are indeed the Macedonians, Albanians and Montenegrins that I have met.

I definitely want to see more of their rich cultural heritage. If, like me, you are interested in European history and culture, I can only encourage you to discover these beautiful countries and their wonderful people.

Around noon, we left Niš and headed on to Macedonia. The highway stretched endlessly towards the horizon.

At Leskovac, the dual carriageway ended and we continued our journey on a very good road. No potholes, not much traffic, but as the road was very curvy, you couldn't drive too fast.

Into Macedonia

On the Macedonian border, a miniature version of the promised Easter holiday traffic jam materialized. There was a line of about ten cars in front of us, and we waited for around twenty minutes. When it was our turn, the customs officer looked at our passports and car insurance, but in no time at all we were allowed to continue our journey into Macedonia. The only slight disappointment was that we didn't get an entrance visa into our passports. As we didn't get one reentering the country from the Greek border either, I suppose the Macedonians simply don't issue any to EU citizens. Pity. :(

Soon after the border, we took the highway to Skopje. Like in Serbia, you have to pay a toll to use them. At the toll booth, we had a rather unpleasant encounter. Several very dirty women approached our car and begged for money. They moaned pitifully and when I tried to ignore them, they gesticulated and lamented ever more forcefully. It was a really embarrassing situation.

Skopje

Finding the centre of Skopje was not at all easy. We left the ringroad too early and ended up in a northern suburb of Skopje. Bumping along badly paved roads, we desperately tried to read the cyrillic street-names and match them to our map. The endeavour was doomed to fail, because, as we finally realized, we were still far off the map. The houses and streets looked, to our Western European eyes, quite poor, but well-kept and peaceful. The people went about their business and hardly glanced at this strange Luxembourgish car that kept veering into small sidestreets to turn around and stopping at street corners to peer up at the facades. Fortunately, the other drivers were careful and laid-back, so our excursion into suburban Skopje didn't cause any traffic incidents. At last we were back on the ring-road, and this time we were clever enough to wait for the “centre”-sign to guide us in the right direction. But finding our hotel still proved a challenge. Skopje is a large city, and if you have no idea were you are, it's difficult to get your bearings. Fortunately, the traffic was relatively slow, compared to Iberian or French standards. I drove, and Sonia took care of the cyrillic street signs. It did help that we can read the alphabet fluently, but deciphering foreign names from across the street is still a challenge. By sheer luck, we had been heading in the right direction and when we finally made out where we were, the hotel was almost around the corner.

The area didn't look too promising. Electric wiring and air-conditioning boxes hung from bleak, crumbling apartment facades. Could this really be the right street? But then we saw the Hotel Premier: a brand new building, spotless and welcoming. Sonia hopped out to check in, while I waited for the garage door to open. Soon she reappeared with the receptionist in tow. She announced cheerfully that he would guide me in. Guide me in? I know how to drive, thank you very much. But then I had a closer look at the opening to the underground garage. The entrance was narrow. Very narrow. I put the car in reverse to get a better angle. Unfortunately, the street was narrow as well. Very narrow. And there were cars parked at both sides. I put the car back into drive. A couple more manoeuvres, and I had managed to wedge myself tightly in between the two sides of the garage entrance. The very steep garage entrance. I started to sweat. This wasn't going to work. The receptionist waved me forward. I anxiously shook my head. Sonia coaxed me on. “Trust him, he knows what he's doing.” But does he know what I'm doing, I thought desperately, and inched forward. Almost immediately, he motioned for me to stop. I'm probably nanometres from the wall, I thought, and put the car in reverse. But I had underestimated the steepness of the descent. The car rolled forward another millimetre. “Stop,” my sister and the receptionist yelled in unison. I jumped on the brake. Now what? If I tried to back out and the car rolled forward again, I was sure to dent it. Shit. “You have to back out,” Sonia explained. No, really? “But turn right really hard, otherwise you'll scratch the back door.” Somebody help me! I was suddenly seized by sheer, existential angst. “Back up,” the receptionist tried to help. My sister repeated the order in Luxembourgish. Great, that's really helpful.

“Don't be afraid,” the concierge added encouragingly. How many people has he told this already, I wondered, while I eyed the scratch marks on the wall apprehensively. Alright, don't think, just do. I pushed the gas pedal, with my right foot still firmly locked onto the brake. The engine howled in protest. “Not too fast, you're really close.” I felt like jumping out of the car and letting someone else deal with this mess. Which by now wasn't really an option, as I couldn't even open the car door one inch without banging it against the facade. “Turn all the way right,” the concierge advised. “Riets,” echoed Sonia in Luxembourgish. How do you turn right? I hung onto the steering wheel with all my force. The tires squealed pitifully. “The other way,” my two guides yelled in unison. Mommyyy!!!

Five minutes later, we were all three laughing the incident off. I had finally managed to get the car out of the deadlock and, without so much as a scratch, down the ramp into the garage. What an experience!

Up on the third floor, our room was simply a dream, even more so than the one in Niš: vast, comfortable, with a separate sitting area and an ultra-large, comfy bed. I collapsed gratefully onto it. After I had recovered from the sobering fact that, just maybe, I'm not such a great driver after all, we were ready to explore the Macedonian capital. The concierge handed us a map of the city and now we realized why it had been so difficult to find our way: a lot of streets had changed their names in the last few years. The perks of a new country, you never get too much of the boring same ole same ole.

From the hotel, we walked towards the centre of Skopje. This part of the town is very modern, with banks, malls, shops, bars and … drugstores. Almost every street seems to have its own apteka, and sometimes you find several of them just a few buildings apart. Could it be that the Macedonians collectively suffered from very bad health, or even that this was a nation of hypochondriacs? Vain musings, and almost certainly unfounded. The people we saw on the street all looked very healthy. Especially the women were very well dressed, sophisticated, modern and often stunningly good-looking. I noticed this all over the Balkans, by the way. More than once, I felt like a bum in comparison.

I really liked the atmosphere of the city. It's a modern capital, but much more laid-back than other European hubs, maybe because of its relatively small size (only half a million inhabitants). The streets aren't congested with cars, either, and the drivers were very careful, at least as far as other vehicles were concerned. It was an entirely different matter for pedestrians, though. Everywhere in the world, it's a good idea for a pedestrian to make sure you're not in the way of a car, but especially so in Macedonia (and Albania, I might add). A pedestrian crossing does not at all ensure that the car will stop for you, so beware! As I'm not a big fan of pedestrian crossings anyway, I didn't mind that particular Balkan idiosyncracy and always managed to cross the street safely. I was also particularly impressed by their traffic lights, which actually count down the seconds until the lights change colours. Now that could be useful in Luxembourg, too!

The city's largest square is Macedonia Square. It's located right next to the Stone Bridge, which leads across the river Vardar to the fortress.

At its south end, Macedonia Square turns into a pedestrian zone, full of trendy bars and cafés. There we also found a museum that documents the life of Mother Teresa, the Albanian nun who was born in Skopje in 1910. We didn't visit the place, though.

The street ends at the old railway station, which was partly destroyed in an earthquake. The entire region is subject to earthquakes, and a particularly violent one struck the town in 1963. The station's clock stopped when the quake happened, and, together with the ruined station walls, it now serves as a memorial of the disaster.

From the station we turned west and soon reached the very impressive Church of Sveti Kliment Ohridski, meaning the Church of Saint Clement of Ohrid. It's a modern Orthodox church, built in 1972, very beautifully designed. When we got there, a mass was celebrated inside. As I'm not an Orthodox Christian, or of any other denomination for that matter, we didn't want to intrude on their prayers and resolved to have a closer look the next day.

By then it was getting dark and the city was bathed in lights. The church, the square, the stone bridge, the fortress, all were beautifully illuminated. To the south of the city lies Mount Vodno and on top of it shone a large cross. This is the Millennium Cross, apparently the largest cross in the world, which was built in 2000 and can clearly be seen from the streets of Skopje.

We were fast becoming very hungry and looked for a place to eat. We ended up in Pelister restaurant on Macedonia Square, and what a lucky find that was! The place had the feel of a very stylish French bistro, and the food was simply delicious. The waitresses were very efficient and friendly and they all spoke very good English. The prices were reasonable, about half what you would pay for a similar meal in Luxembourg.

Judging from how busy the place was, the locals seemed to appreciate it as well. Another thing I liked about Macedonian restaurants: most (or all?) of them seem to be non-smoking, and the patrons actually respect this, even in small rural restaurants, as we noticed a few days later.

After a very satisfying meal, we walked back to our hotel. The streets were quiet but not deserted and we never felt the least bit queasy or threatened. The area around our hotel, which we had first eyed suspiciously, revealed itself on closer inspection as an ordinary (and blissfully quiet) residential neighbourhood. This holds true for the whole of Macedonia and Albania: we felt very safe everywhere, even late at night.

Soon after, we dozed off happily, looking forward to another eventful day in Skopje.